Never heard of tapering before. After some google search I find the following:

‘a progressive nonlinear reduction of the training load during a variable period of time, in an attempt to reduce the physiological and psychological stress of daily training and optimise sports performance’.

What's the difference between taper and deload, they look the same.

Thanks

Taper is more of a sports training term, deload more for weights if you want to get anal

For lifting, say squat/deadlft, people who can lift very heavy loads like 700-1000+ lbs can take up to 2-4 weeks to recover from their last heavy session, so they spend those weeks leading up to a meet/test doing light/medium workouts to recover and peak.

Can be acomplished by reduced volume and load/intensity.

But usually intensity is kept fairly high with a big reduction in volume, and hope muscle mass doesn't drop off

Look up fitness/fatigue theory/model, and it will make more sense

https://medium.com/@SandCResearch/what-is-the-fitness-fatigue-model-6a6ca3274aab

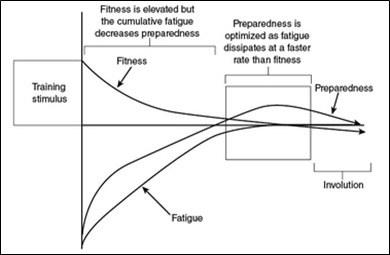

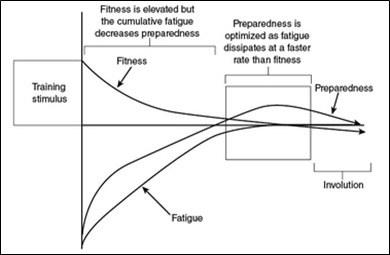

The traditional fitness-fatigue model starts with the observation that performance tends to reduce immediately after a workout, and stays reduced for up a few days in some cases. Yet, after the initial reduction, there is a rebound, and performance then improves.

The fitness-fatigue model explains this curve by proposing that it is the sum of two curves, one representing the fatigue effect, and the other representing the fitness improvement. Only once the fatigue effect has dissipated is it possible to see the fitness effect, even though fitness has actually been improving from immediately after the end of the workout.

Without the fitness-fatigue model, we could easily fall into the trap of believing that the fitness adaptations to a workout only occur after a couple of days, because of the reduction in performance. In fact, adaptations probably occur very soon after the workout itself.

What is “fitness” in an updated model?

The traditional fitness-fatigue model does not take into account newer research showing that strength can be positively affected by transient changes in the ability to produce force, as well as by long-lasting adaptations.

Long-lasting changes in strength involve adaptations inside the central nervous system or muscle-tendon unit, such as increases in voluntary activation, or increases in muscle size.

Transient improvements in the ability to produce force occur because of potentiation, which may also involve changes in either the central nervous system or inside the muscle.

Potentiation has most often been observed to occur immediately after a strength training workout, where it is referred to as the “post-activation potentiation” effect. Even so, potentiation can also be recorded several hours or even days after a workout. It is typically only seen when fatigue is minimal, such as after training with light loads and fast bar speeds.

Thus, in an updated fitness-fatigue model, we should refer to multiple fitness effects, some of which reflect long-lasting adaptations, and some of which reflect short-term potentiation.

In the traditional fitness-fatigue model, the temporary increase in fatigue that causes transitory reductions in performance was not well-defined, because of a lack of research in the area. Yet, the fatigue and recovery literature has developed substantially since the fitness-fatigue model was first suggested.

Research into recovery has shown that there are three factors that cause transient reductions in strength after a workout: (1) peripheral fatigue, (2) central fatigue, and (3) muscle damage.

Peripheral fatigue after a strength training workout is largely caused by the accumulation of metabolites, and its effects are dissipated within hours. Similarly, central fatigue is extremely transitory, and is rarely seen beyond an hour after a strength training workout (except when it occurs subsequent to severe muscle damage).

Muscle damage can produce reductions in strength that last for up to weeks in some cases, where the damage to the muscle is severe. More commonly, however, the reductions in strength because of muscle damage last only a couple of days.

Thus, in an updated fitness-fatigue model, we should refer to multiple fatigue effects. Also, we should be clear that peripheral and central fatigue usually reflect effects lasting only a few hours, while muscle damage reflects a longer-lasting effect, and is likely the primary determinant of losses in strength on the day or days after a hard workout.

I looked up tapering and came across a lot explanations and graph and it is an amazing concept but hard to get right just before the meet/competition especially amount of tapering for i.e. Olympic trials compared to actual Olympic games. This is where I have been going wrong, I just work and work and work, with a day or two rest between each week. that's why fatigue has been building up and even though the fitness has been going up and feel strong for each session, the performance during testing is not high it's actually low, but recovering from fatigue while maintaining routine to get stronger.

They mentioned the concept of overshooting phenomenon, a result of tapering in power demanding sports. But it's hard to implement in shorter sprints then it is with long distance running.

But great information, thanks.